The annual festival of San Fermin in Pamplona, Spain, begins tomorrow. I was in attendance in 1994, 1996 and 2000, and stayed for the whole gala (it ends on the 14th each year) in 1998, when the following was written. My cousin Don is there again this year.

The annual festival of San Fermin in Pamplona, Spain, begins tomorrow. I was in attendance in 1994, 1996 and 2000, and stayed for the whole gala (it ends on the 14th each year) in 1998, when the following was written. My cousin Don is there again this year.----

More than seventy years have passed since Ernest Hemingway decided to borrow a largely unknown religious festival in a dusty Spanish market town and to use it as the setting for the critical second half of his first successful novel, The Sun Also Rises.

By doing so, he brought the town of Pamplona and its annual celebration, the Fiesta del San Fermin, directly into the gaze of the English-speaking world.

For Anglos, particularly Americans, Hemingway provided a behavioral framework for a prototype of intelligent, self-aware "expatriotism" that has endured up to our own time. In his novel, first in Paris and then in Pamplona, foreigners who are respectful of local colors and traditions are contrasted to fellow countrymen who are overseas for all the wrong reasons, and who don’t understand why Paris is not Peoria.

More specifically, Hemingway established the drinking norms for several generations of travelers. It may not seem like that much of an innovation now, but when I first read Hemingway in the early 1980’s, I marveled at how cool it was for his characters to be drinking wine with meals. Imagine the effect on readers in America in the 1920’s, during Prohibition, of incessant apertifs, teeming sidewalk cafes and sweaty pitchers of cool lager beer in the hot Iberian sun.

To be sure, the behavior of expatriates has been defined and expanded by many books and films, but The Sun Also Rises remains at the head of the list, if for no other reason than the ongoing existence of San Fermin. Each year, the festival affords Anglos the opportunity to walk, talk and drink like Papa, and in many of the same places he did. I’m no exception. In 1998, during my third visit to Pamplona for the festival, I thought about it quite a lot – at least when I was sober, which was seldom, and which itself puts me right back in Papa’s formidable track.

My observations aren’t designed to be comprehensive, and I’ll say little about the bulls and the bullfights. This is an oversight, albeit an intentional one, although I’ll begin with a small bit of ephemera related to the bulls.

July, 1998 found four and sometimes five foreigners (three Americans, a New Zealander and a Frenchman) sharing a bare-bones apartment for the eight-day duration of San Fermin. Other foreign friends and acquaintances encountered during the festival were a number of Englishmen (some firmly aristocratic and of the old school, and others the obvious products of entrepreneurial Thatcherism), as well as Swedes, Finns, Germans, a resident of Andorra, and of course a good many fellow Americans.

My little group arrived two days early, having traveled from Warren Parker’s home near Perpignan (on the Mediterranean) by car to the Atlantic resort city of Biarritz. Like Jake Barnes in Hemingway’s novel, we drove across the border from France, through the Pyrennees, right into Pamplona’s central Plaza del Castillo for drinks.

We left town on the morning after the festival’s last day, so for the first time, I was able to witness the atmosphere from beginning to end.

Once the festival started, and as modern day interpreters of the Hemingway tradition, we took our obligations very seriously. Disregarding the previous evening’s pain, I’d set my watch to beep at 7:35 a.m. This would give me enough time to throw on some clothes, hang tight as the elevator took me down to street level, dash down the block and into the bakery on the corner, and snag pastries.

Meanwhile, Don Barry would be heating water for instant coffee. At eight, we’d gather around the living room table, sweeping aside the last evening’s cigarette butts and bullfight ticket stubs, and watch the running of the bulls on television.

That’s right, on television. Before anyone jumps me for not running, I’ll remind all of you that Hemingway himself never bothered. I’ve come up with three very good reasons why I don’t run with the bulls. First, it would be hard to avoid spilling my drink. Second, the route is several hundred meters long, and I couldn’t run that far drunk, sober or anywhere in between. Third, I’m a coward.

I’ve no idea what Hemingway’s excuses were.

One morning I did make it out for a walk fairly early. The crews were sweeping and hosing down the streets. Many locals were preparing to dive into San Fermin, and just as many were on their way home for a nap before hitting it again.

In one of the plazas in the old part of town I saw a little boy riding high on his father’s shoulders. Both were wearing white cotton pants and shirts with matching red scarves and sashes.

One of the perpetually marching bands was rounding the corner, and the child was giggling in step with its discordant progress. Seconds later the Gigantes (huge puppets on the backs of men) emerged from the same alleyway. The laughter stopped and his eyes grew wide in confusion. He held on to his father’s neck as if to choke him for bringing him into contact with these huge, strange figures.

Primitive man, I thought. Simplistic awe at the unexplainable, these elongated "giants" becoming symbols of power and authority, to be feared and worshipped.

Perhaps not. Recovering from his initial shock, the child took his cue from the crowd and reverted to festive mirth. The Gigantes weren’t threatening at all. They danced in the plaza with the band, and moved on to the next crowd. I was left to ponder the many aspects of San Fermin that have eluded me.

Another time we were in a bar feasting on tapas (tasty bar snacks) and draining small glasses of the rather uniformly adequate Spanish beer. Everything that wasn’t bolted down had been removed: Smoke-edged rectangles on the wall showed where pictures usually hung, and scuff marks on the floor the location of tables and chairs. All had been taken away until the end of the festival, but at least the beers still were being served in glass. People were singing and dancing, and the bartenders were trading glasses and bits of food for pesetas in rapid-fire fashion. Spanish bar etiquette is a wonderful thing, even at the peak of San Fermin’s madness.

Warren and Reggie bantered with the workers in Spanish. Our bill was lower than it should have been. We objected, and the proprietor waved us off.

Outside, basking in the sunlight, it occurred to me that I was "tight". Hemingway used the word freely throughout "The Sun Also Rises." The characters debate the merits of being tight. They’re hardly ever without a drink. They’re hardly ever not tight. During the festival, tightness is an epidemic.

In 1998, my favorite place for getting tight was the Meson del Caballo Blanco, a bar perched atop the city walls off a narrow street that sneaks into the maze of elderly buildings by the cathedral. The stone building that houses Caballo Blanco is very old and dignified, and the effect of drinking in the small barroom at ground level is that of drinking in an old chapel, which it might well have been at one time.

During the festival, Anglo expatriates typically hold several parties in the small pedestrian plaza in front of the Caballo Blanco, from which one can look out beyond the ramparts and into the valley. Although the valley is rapidly being filled with housing blocks as the modern city expands, it’s still an excellent view, and it isn’t hard to imagine it the way it appeared during Hemingway’s day.

Once, after one of these gatherings began to degenerate, Don, Warren and I slipped into the Caballo Blanco and began drinking beer. I enjoyed a few rations of Pacharan, which is a liqueur native to Pamplona and the province of Navarra, and inexplicably is something that wasn’t mentioned by Hemingway. In inexact terms, Pacharan is rather like a wine-based schnapps flavored with anise and sloe berries. Two years before, I’d been introduced to Pacharan by Arthur and Maria Burton, with whom I roomed and shared numerous rounds of the liqueur along with black coffee.

Standing at the bar of the crowded Caballo Blanco in mid-afternoon, filled with the bread, salami and cheese from the party out in the plaza, cradling a Pacharan, all was relatively peaceful. Suddenly a group of Basque men from France began singing traditional songs in the obscure and lovely Basque tongue. Drinks were bought and exchanged as the singing continued. At some point, the day disappeared and I was in another place and time. I was tight. We hopped from bar to bar in the old part of town. The rest is hazy.

There are numerous stories to tell. There was the "pig walk," an excursion to a restaurant specializing in roast pig led by a wheeler-dealer British ex-Shakespearean actor that included a long layover (both coming and going) in a bar (the Savoy) where I had the best gin and tonic of my life.

There was our trip up into the mountains with Arthur and Maria, to the town of Aoiz, where we enjoyed an outstanding multi-course meal, and there were a half-dozen other fine culinary experiences that rarely cost me more than $25, wine and service included, for quality at twice the price.

There were times spent watching the scalpers work in front of the bullring, the dancing and singing in the parks and pavilions, and the long-suffering sanitation workers blasting and hauling the refuse. There were so many of these times, and most of them were good.

I began this piece intending to discuss San Fermin and the phenomenon of expatriates who follow in the wake of Ernest Hemingway by returning to Pamplona each year. I was going to take the critical view and expose some of them for the frauds they are, and others for the boors they are, and yet as I wrote, I found my attitude mellowing at the memory of the good times I’ve had during the festival. Most of the expatriates I met were neither frauds nor boors. They merely were enjoying the festival in the only way they knew, which sometimes seemed harmonious and sincere, and other times not.

In the end, perhaps the best thing about San Fermin is that it still belongs to the people of Pamplona and Navarra in spite of the presence of legions of foreigners, many of whom wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between Ernest Hemingway and Ernest Borgnine, or be oblivious to the existence of both, or be far too intoxicated (not tight, mind you) to care.

Perhaps I’m being overly sensitive about the whole phenomenon, for as much as I’d like to be one of the knowledgeable expatriates, the fact remains that in three visits to San Fermin, I haven’t really surrendered myself to the local euphoria. I’ve remained aloof, analytical, foreign, and very much on the outside, looking in.

Then again, most of the foreigners who come to Pamplona for the festival, then as well as now, are on the outside, looking in – even those who pride themselves on preserving the Hemingwayesque "traditions." Many of them are perfectly well-meaning. They’re older now, and they see themselves both as inheritors of a noble heritage of foreign presence in Pamplona and guardians of it. To them, the youthful Americans and Brits partying in the streets – wine stained, hormonal satyrs staggering past the dark huddles of Euro-trash – are entirely lacking in proper understanding.

Sadly, the older generation doesn’t do much to share their inheritance. I disagree with their view of the young people who are coming to Pamplona now and discovering San Fermin for the first time without the legacy of Hemingway and James Michener to weigh them down.

Somewhere, perhaps in a campground on the outskirts of the city or in a flat downtown, where a dozen arrivals sleep atop their packs and each other, there’s a 22-year-old American who’ll be stepping out into the madness and befriending a native, playing with Pamplona’s children, eating mixed salad and bean soup, drinking Tinto, being led into the chapel cellar for a look at the relics, managing to learn a sentence in Spanish and two in Basque, kicking around a soccer ball, and completely forgetting that there is a world outside Pamplona during festival time.

In eight days, this new American devotee of San Fermin will never even meet one of the classically trained expatriates – and be all the better for the omission.

There’s a place for both, I guess, and I know where I’ll probably be.

On the evening of the festival’s last day, Don and I arranged to meet Ray Mouton at the Café Iruna, which featured prominently in The Sun Also Rises. Appropriately, Ray is a writer. More importantly, he is a witty, engaging and fascinating person who might well be the only legitimate contemporary keeper of the flame insofar as the expatriate community’s knowledge of and respect for San Fermin’s traditions are concerned.

Ray neither suffers the fools among the expatriates gladly, nor does he speak Spanish or Basque and become totally immersed in the local scene. He loves the bulls. He floats along the periphery of San Fermin, pausing occasionally to offer a pithy comment, participating when he feels like it, and remaining alone when he doesn’t. He’s an original, and I love him dearly for it.

We were to have dinner together. Ray, quite possibly the only teetotaler ever to enter the city limits of Pamplona and survive to tell the tale, finished his orange soda. He paid and tipped the waiter. The three of us began walking toward the spot adjoining the city walls where a street comes up the hill and the bulls are penned prior to their daily run to the bullring and their destiny.

The final bullfight was over, and the pens had been removed, a fact we observed as we ascended a narrow cobblestoned walkway leading to the top of the wall. There we were greeted with a cool, mournful, cleansing breeze and a vivid orange sunset hugging the gray tops of the mountains and framed by the black, infinite night above us.

Below, in the now populated and modern valley, so few electrical lights had yet to be switched on that a comforting illusion of nature was conjured. Behind us, Pamplona was strangely quiet after eight days of chaos. The city felt spent. The curtain seemed to be dropping. Ray, Don and I walked slowly along the deserted city walls, lingering in the rushing air that carried the festival away to be refreshed for the following year, into the park near the citadel, to a restaurant where we were the only customers. As we ate, drank and talked, we heard the fireworks that brought San Fermin to a close.

That’s as good as it gets, expatriate or not. It was a good run. Let’s do it again someday.

France’s proudest original beer style was traditionally made by farmers in the beer-loving north of France, near the border with Belgium. Brewed in the colder months of late winter and early spring, it was bottled in wine and champagne bottles, then laid down in cellars to be shared with family and friends in the warm months, when the heat made brewing impossible. The beer had to be strong and hardy enough for cellaring, yet light and refreshing enough to quench a farmer’s thirst at the height of the summer.

France’s proudest original beer style was traditionally made by farmers in the beer-loving north of France, near the border with Belgium. Brewed in the colder months of late winter and early spring, it was bottled in wine and champagne bottles, then laid down in cellars to be shared with family and friends in the warm months, when the heat made brewing impossible. The beer had to be strong and hardy enough for cellaring, yet light and refreshing enough to quench a farmer’s thirst at the height of the summer. Sincere thanks to all in attendance, and to Dave and Dave, proprietors of bNA, for making this event possible. Even more appreciation is due those who joined us for the bicycle ride earlier in the afternoon. See

Sincere thanks to all in attendance, and to Dave and Dave, proprietors of bNA, for making this event possible. Even more appreciation is due those who joined us for the bicycle ride earlier in the afternoon. See  This dinner and beer tasting evolved in a very spontaneous fashion, given the desire of the Daves to stage fun events, multiple cases of Bieres de Gardes stacked in the Rich O’s storage area, and the overlap of Bastille Day with the Tour de France, which a few of us have witnessed while riding our own bikes in the vicinity. All these factors came together, and a fine time was had by all.

This dinner and beer tasting evolved in a very spontaneous fashion, given the desire of the Daves to stage fun events, multiple cases of Bieres de Gardes stacked in the Rich O’s storage area, and the overlap of Bastille Day with the Tour de France, which a few of us have witnessed while riding our own bikes in the vicinity. All these factors came together, and a fine time was had by all. The idea was to spend little time on tasting notes and beer descriptions, but to have a good time. I speak no French, and in truth, have little idea how to pronounce the names of the beers, but that didn;t seem to matter. We were not overly concerned with proper glassware,and pourings were expanded from an original goal of four ounces to six ounces for each of the nine ales (except the closing splash of Pome).

The idea was to spend little time on tasting notes and beer descriptions, but to have a good time. I speak no French, and in truth, have little idea how to pronounce the names of the beers, but that didn;t seem to matter. We were not overly concerned with proper glassware,and pourings were expanded from an original goal of four ounces to six ounces for each of the nine ales (except the closing splash of Pome).

Artemsia Ale ... brown ale brewed with 80% Simpson's Golden Promise two-row and molasses, and flavored with mugwort (the "dream herb," related to sagebrush and a cousin of wormwood), sweet orange peel and chamomile. 4.5% abv.

Artemsia Ale ... brown ale brewed with 80% Simpson's Golden Promise two-row and molasses, and flavored with mugwort (the "dream herb," related to sagebrush and a cousin of wormwood), sweet orange peel and chamomile. 4.5% abv.

Here are Dave’s thoughts on the matter, as copied from his blog.

Here are Dave’s thoughts on the matter, as copied from his blog.

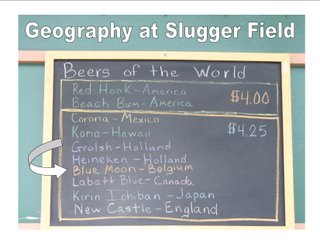

Last Saturday evening, I accompanied Mrs. Curmudgeon to an exciting baseball game at Louisville Slugger Field, where the hometown Bats rallied from behind to defeat the Columbus Clippers.

Last Saturday evening, I accompanied Mrs. Curmudgeon to an exciting baseball game at Louisville Slugger Field, where the hometown Bats rallied from behind to defeat the Columbus Clippers.